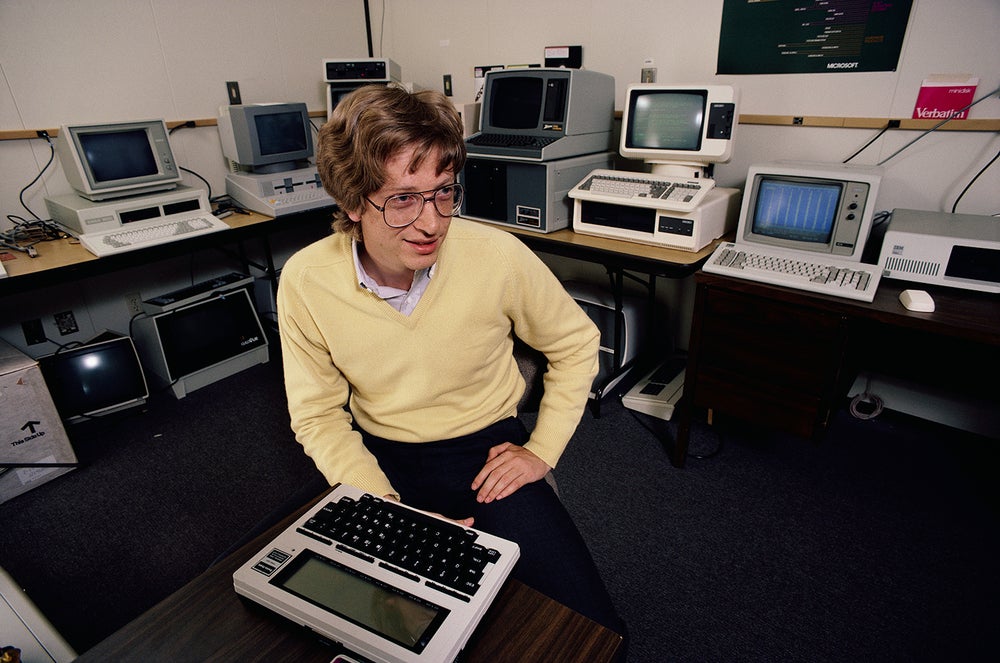

On April 4, 1975, two young programmers changed the course of technology with a decision that seemed small at the time. Bill Gates and Paul Allen had created a version of the BASIC programming language for the Altair 8800, an early microcomputer built for hobbyists. The sale of that software marked the first official business transaction in the history of Microsoft. That day became the company’s founding date.

The program they delivered was small. It occupied less than 4 kilobytes of memory. It had no graphics, no mouse, and no sound. Yet it served a very specific purpose. It allowed the Altair to become programmable. That meant anyone who owned the machine could now write instructions, run commands, and create their own software. That access, previously limited to universities and corporations, opened a new era.

A Startup Without a Product or Office

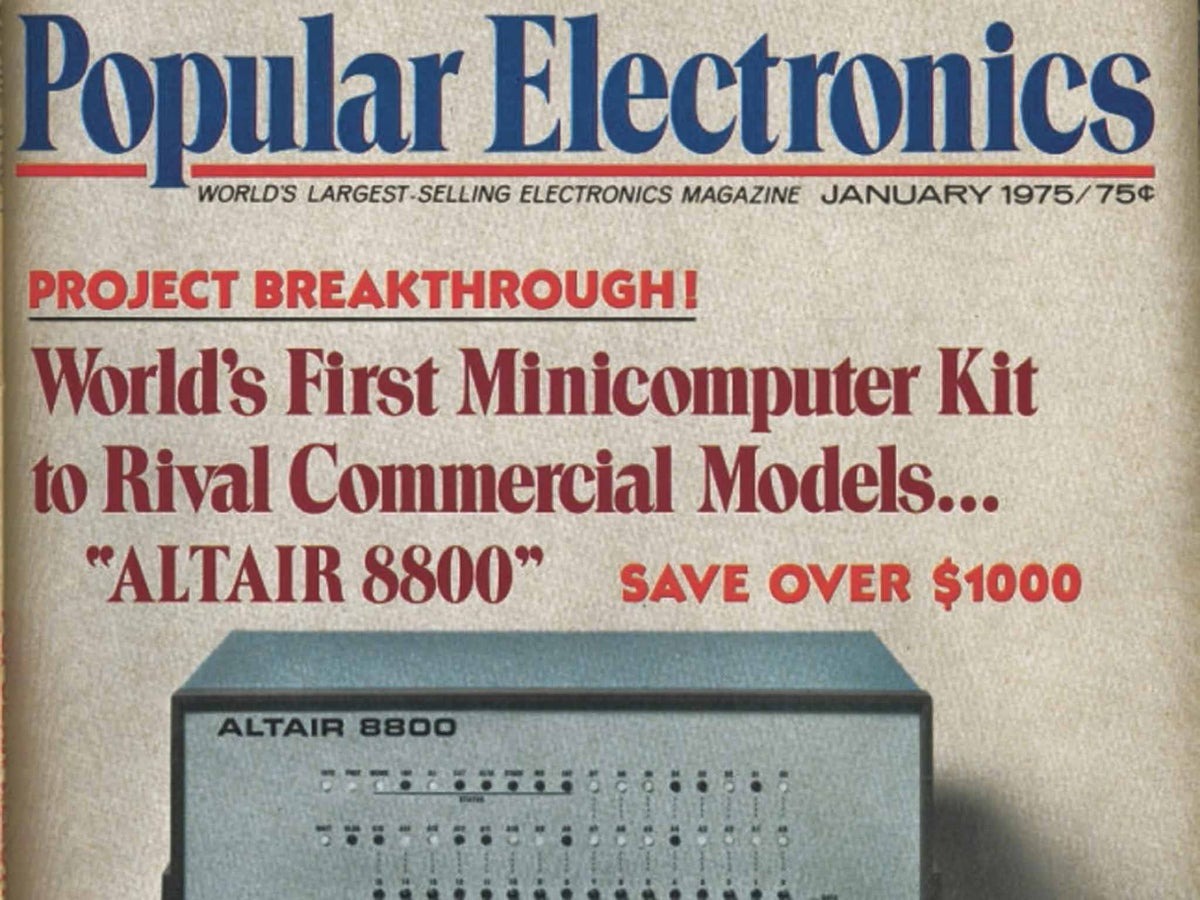

Paul Allen had seen the Altair 8800 featured in Popular Electronics. He immediately understood what it represented. This was not a hobby toy. This was the first microcomputer available to the public at a price that individuals could afford. He showed the magazine to Gates, who was still a student at Harvard. They both recognized the potential. They also saw a gap. The machine had no software.

They reached out to the makers of the Altair, a company named MITS based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Allen placed the call. Gates handled the pitch. They told MITS they had a version of BASIC ready for the Altair. That was not true at the time. They had no working software. They had not even seen the machine in person. But they knew they could build it.

They started writing the code using a PDP-10 mainframe at Harvard. They created an Altair simulator to test their work since they had no access to the actual computer. Over the next eight weeks, they built the full interpreter. It worked.

What Made Altair BASIC So Important?

First useful language for early hobbyist machines

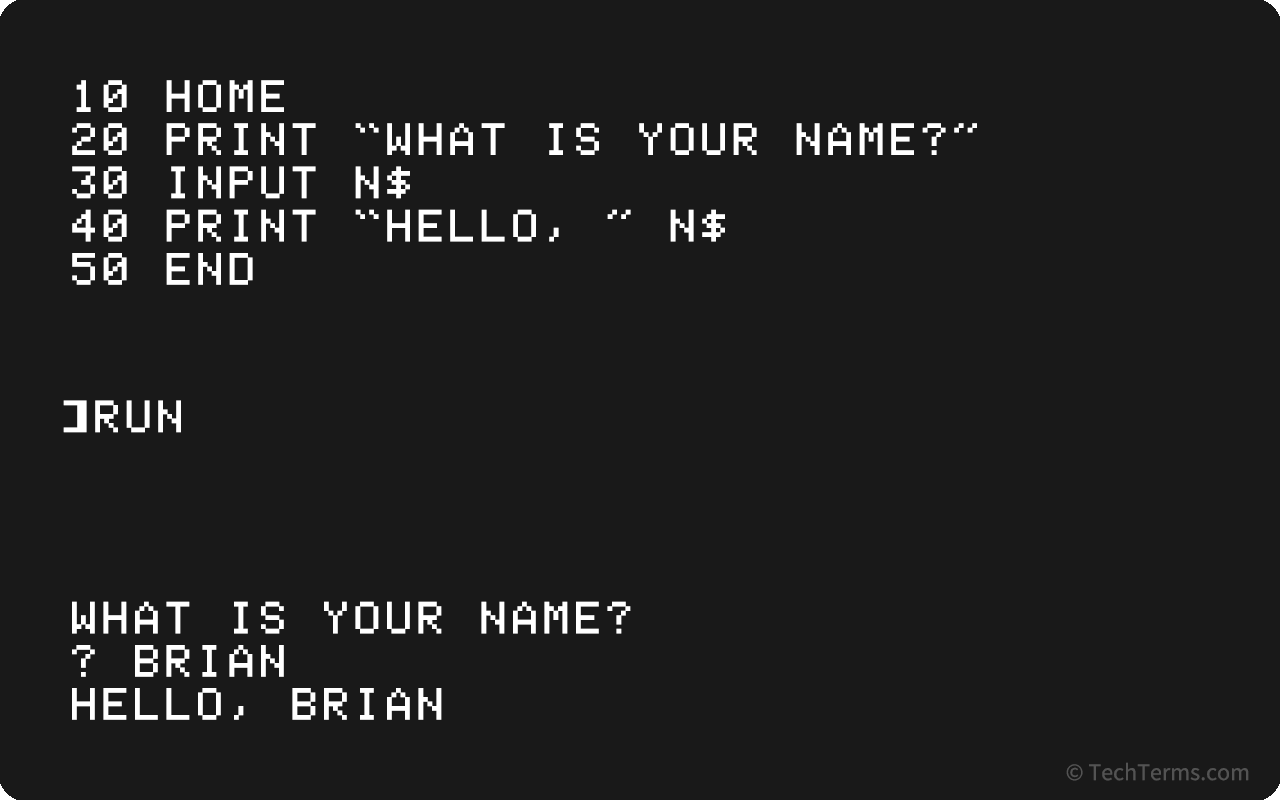

The Altair 8800 launched with no user interface. Owners interacted with it using physical switches on the front panel. Altair BASIC changed that. It allowed anyone to write commands using human-readable language.

Technical details

- Memory use: 4KB

- Language: BASIC interpreter

- Input method: Teletype

- Storage: Paper tape

With this interpreter, users could perform math, run loops, store variables, and write small programs.

Most importantly, they could now do more than look at blinking lights. They could experiment, create, and explore the machine’s capabilities.

April 4, 1975 – The Deal That Launched Microsoft

Gates and Allen flew to Albuquerque. Paul Allen carried the paper tape containing the software. They met with MITS founder Ed Roberts. They loaded the code into the Altair. It worked on the first try. That successful demo led to a licensing agreement. MITS agreed to distribute the software as part of the Altair system.

Microsoft was formed on that date, and Altair BASIC became the company’s first commercial product. That agreement turned an informal partnership into an actual business. They opened a small office in Albuquerque to stay close to MITS and continued writing software for microcomputers.

Gates Was Paid Per Copy, Not Per Hour

At first, software piracy was rampant. Hobbyists shared Altair BASIC freely. Microsoft saw no revenue from many of the early copies.

Gates wrote an open letter to computer hobbyists in 1976. He asked users to pay for the software they used. That letter remains one of the earliest arguments in favor of software copyright.

Microsoft: Then and Now

| Category | 1975 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|

| Headquarters | Albuquerque, New Mexico | Redmond, Washington |

| Employees | 3 | Over 220,000 |

| First Product | Altair BASIC | Copilot, Windows, Azure, Xbox |

| Annual Revenue | Less than $20,000 | Expected over $230 billion |

| Notable Clients | MITS | Governments, Fortune 500, schools |

| Key Focus | Programming languages | Cloud, AI, productivity software |

The Code Still Echoes

BASIC influenced many languages that followed. Concepts like variables, loops, and conditionals became familiar to an entire generation of self-taught programmers. For many developers, Altair BASIC was their first experience writing code. It taught logic, structure, and precision.

Microsoft carried that philosophy forward. Even as it entered new industries—operating systems, gaming, artificial intelligence—the idea that software should be accessible, scalable, and licensable remained at the company’s core.

A Legacy Still Growing

On April 4, 2025, Microsoft will acknowledge 50 years since that first deal. But the real celebration is in the shift it caused. That one program, sold for a few hundred dollars, introduced the idea that software could stand as a product of its own. Bill Gates is one of the richest and most popular names in the world.

Today, the company’s tools support everything from hospitals to space agencies. Altair BASIC taught Microsoft that a good product, delivered with precision, could change the direction of an industry.

Fifty years later, the evidence is everywhere.